Space | Action | Movement: Understanding Composition as Architecture

(presented 24

March 1999 | CCCC 1999 | Atlanta)

Johndan Johnson-Eilola

Clarkson University

Space | Action | Movement: Understanding Composition as Architecture(presented 24

March 1999 | CCCC 1999 | Atlanta)

|

|

The very heterogeneity of the definition of architecture--space, action, and movement--makes it into that event, that place of shock, or that place of the invention of ourselves. The event is the place where the rethinking and reformulation of the different elements of architecture, many of which have resulted in or added to contemporary social inequities, may lead to their solution.

Bernard Tschumi, "Six Concepts," p. 258

We have long understood the term writing as simultaneously an object and an event. We do writing, we are writing texts, we are reading a piece of writing, we are talking about a writer's writing, things that were written and are also, simultaneously, writing.

But while the term "writing" seems to do a wonderful job of capturing both object and action--what Louise Phelps once termed both the dancer and the dance--we still continue to treat those artifacts--the objects of writing, as relatively inert and external objects. In other words, we have succeeded in articulating the term "writing" as either an action or an object, we have done less well in thinking about writing as a space in which action takes place. We have done less well in teaching our students (and ourselves) to think about writing as spaces for collaborative action. We have done less well at replacing the either/or with the and/and/and, as Deleuze and Guattari (among others) put it.

There are two (or at least two--I'm sure there are more) there are at least two immediate and related exceptions that come to mind when I make that observation: online collaboration and hypertext. Each of these have important things to offer in the project I'm outlining here, even if they don't go far enough (to my way of thinking), and have different things to offer.

Exception 1: Online Collaboration

Let me take online collaboration first, because that offers us a space in which people come together to do writing as an action. Writers, in collaborative space, meet in real time or over time to discuss projects, to critique works, and, sometimes, to produce texts. In one way of thinking, right there we have the union of object and action. Numerous researchers have pointed out the ways that students can use online collaborative spaces to negotiate meaning in texts, to contest each others' meaning, to bring together object and action in a single, collaborative space.

But if we hang around in these spaces for a little longer, if we begin to consider the text that was produced, the text becomes less action and more object, the action becoming something like the act of throwing a stone into a pond, where splash becomes ripple becomes glassy surface.

This is overstated, of course, and ignores the wide body of theory and practice that has shown us that readers, in numerous ways, actively produce the text. Readers re-animate the object, remake the object, contest it, misread it, argue with it, join their voices to it. And this is true, as far as it goes. But I don't think it goes far enough. For the text itself is, visibly, a static object while the reader's work with the text--the action--is mental. Or, even when the reader marks on the text or writes a counter text, the text still remains static, an object. Object and action remain separate.

Exception 2: Hypertext

Which brings us immediately to the second exception to my complaints about writing being either object or action rather than object and action: hypertext. In hypertexts, in some cases at least, we see text as simultaneously object and action, as readers make active choices in their navigation through a text, choices that affect the ways that the text means. In some cases, in fact--and increasingly on the World Wide Web--these texts allow readers to not only affect their individual concrete reading, but also to affect the shape of the text itself for other readers by adding their own contributions--links, new nodes, commentary, and more. None of this is very new, of course, but I think it can be articulated to a larger project that has sort of stalled.

I need to stop here to make a segue into my real point--I'm finally getting to it, I swear. I knew that waiting until Wednesday night to write my paper would pay off, because Jay said something yesterday afternoon that provided the keystone needed to bring this talk together, or at least as "together" as I ever get. Jay, yesterday at the IP Caucus meeting, introduced a comment about hypertext by joking, "Hypertext ... do you remember hypertext?" In other words, hypertext had a lot of promise but that promise has, in many ways, largely evaporated.

But, still, these texts do not go far enough. Or, maybe they go too far. I haven't decided yet. But let me explain what I see. In hypertext, we create a writing that is simultaneously an object and an action. The text itself, continually undergoing change, can be thought of--read as, written as--an ongoing activity rather than the production of a static textual artifact. Here's the problem, as my tiny mind sees it: We have succeeded in making the text simultaneously object and action, in visible and fluid ways. But in doing so, we have come to unite our actions on the text and in the text so closely with the form of the text that we, in fact, tend to worship the text itself outside of any other purpose. This is, in fact, Hegel's definition of architecture: anything in a building that "did not point to utility" (Tschumi, Architecture, p. 32). Mark Wigley covers this territory in depth in his amazing discussion of the relations between philosophy and architecture, The Architecture of Deconstruction: Derrida's Haunt. Derrida has been active in architectural theory and practice, working extensively with architects and architectural theorists such as Bernard Tschumi, who I draw on heavily later on in this talk.

In a surprising way here, then, architecture here becomes the Derridean "supplement," the meaning outside of the text. And this is what I want to talk about today (at last): writing or textuality as postmodern architecture.

What interests me about postmodern architecture (aside from how much money a postmodern architect makes) is the ways that postmodern buildings have both form and function, even if the two are not related to each other. Postmodern architecture, like writing, is both an action and an object. As Bernard Tschumi, the Dean of the Graduate School of Architecture at Columbia infamously put it, there is no architecture without event. In many ways, architecture is coming at the object/action split from the opposite direction that composition is coming at it from. Today in composition theory and practice, we are moving from writing as an activity to writing as a space--in the work of theorists and teachers using postmodern geography (Sullivan and Porter; Lopez; Cushman) and computers and writing, in particular MOO theory and practice, which I'll come back to in a while as a third and most promising exception (Haynes and Holmevick; Grigar and Barber; Maid; Blythe). At the same time, architecture is moving from the deterministic hierarchy of "form follows function" to a postmodern architecture--or, more accurately, deconstructivist architecture--that allows both form and function, but negates the automatic connection between the two. In another way of thinking, then, postmodern architecture gets at what I claimed was my goal here: to think of writing as both an object and an action, without falling into the trap of seeing the object as the total focus of action. In postmodern architecture, as theorists and practitioners like Koolhaas, Venturi, Rauch, and Brown, and Tschumi articulate it, architecture is both space and action--but the actions are not necessarily determined automatically by the space or relate primarily to the space as a form of building (or textual) worship.

I'd like to end here almost before I've really begun, with some unfortunately general directions for additional thinking, working, and learning in texts as postmodern architecture. Earlier I made the distinction between text as functional architecture and text as postmodern architecture. I don't want to negate the importance of those functionalist approaches--information architecture, for example, will continue to grow in importance as increasing amounts of our lives are spent online. But I want to add to those beginnings by positing six concepts for a postmodern architecture of textuality, drawn from Tschumi's essay, "Six Concepts," in Architecture and Disjunction. Tschumi here attempts to frame a response to Vince Scully's dismissal of postmodern architecture as 'a moment of supreme silliness that deconstructs and self-destructs' (qtd. in Tschumi, "Six Concepts," p. 228).

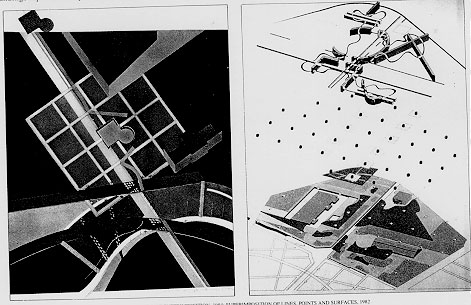

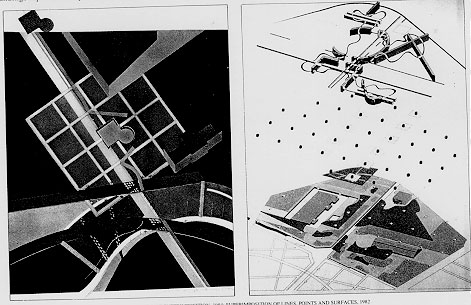

Architecture Text make the visible the familiar (uncanny) large antenna on Guild House reading &writing space overcome information overload/numbing (japanese architecture: locomotive, robot) visuals in textual space, animation (multimedia) deconstruction Glass Video Gallery, Portman's LA Bonaventure Hotel deconstructing hypertext layering representation (across time, subject, etc.) Eisenman's sketches for Arts Center, Tschumi's sketches for Parc de la Vliet texts laid across each other (not linear series of quotations, but overlapping) juxtaposition of different activities in same space weddings in zoos, art museum WAC, odd rooms in MOOS putting people in action in spaces backlash against Le Courbuiser's photographic techniques (people-less) inhabit (nearly literally) texts

This table condenses, in an overly simplistic way, Tschumi's six concepts for postmodern architecture and maps them against textual possibilities.The textual object/events that I discuss are of relatively recent introduction to composition theory and practice, but I think they're readily available to most of us (if they're not, feel free to contact me after this and I'll point you in some general directions that might help). So in the handouts I've concentrated on providing some examples from architecture that you may or may not be familiar with, especially in the contexts and purposes that Tschumi's six categories would put them.

The bulk of the discussion--and in fact, of this paper--lies under the table links. Click for more.

So here I finally am, at last making my point, the last point of this space and of this talk, in a verbalization that is both an act and an object, but in its very presence disappearing like the Chesire Cat: This is what a postmodern architecture of textuality can give us: a space for us, together, to make ourselves and each other and the world.